Straddling the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the city of London was a bubbling pan of scientific will and desire for innovation, especially in the field of watchmaking. It was here that George Graham was able to give free rein to his immense talent as a watchmaker, and to offer the world its high-precision watchmaking mechanisms. Generous and altruistic, the man affectionately known as “Honest George” wanted neither money nor celebrity: he had eyes only for the progress of science and the benefits that humanity could derive from it.

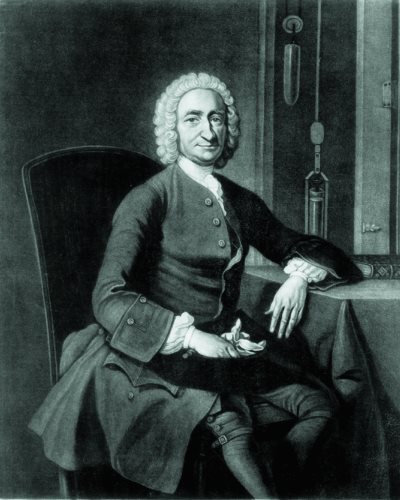

George Graham: the mechanics of the heart

George Graham’s life is inseparable from that of the man who was his mentor and friend, Thomas Tompion. First collaborator Tompion from 1695, Graham became his partner (around 1711) before taking over after the death of the master. By marrying one of his mentor’s nieces, Elizabeth, in 1696, he also became a member of the family. Their professional and friendly relationship was so intimate and so strong that on his death Graham was buried alongside Tompion in Westminster Abbey, an honor traditionally reserved for high-born personalities.

Did Graham find a substitute father in Tompion? It is in any case after the death of his that he leaves his hometown of Kirklinton, where he was born on July 7, 1673 in a family of Quakers. At age 15, having joined London, he became an apprentice with Henry Aske for seven years. His work is so impressive that it attracts the attention of the famous Thomas Tompion, a huge watchmaker who became famous for the production of serial watches, all numbered. Graham joined him in 1695 and began a long history of collaboration and friendship. The young man has both the influence of his mentor and the unique context of the city of London at that time – the place to be when you were interested in far away from watchmaking mechanisms.

When Tompion died in 1713, he entrusted Graham, by will, with the reins of his business. Completely free from his movements, Graham effectively mixes his taste for innovation and his precision timekeeping technique to improve existing mechanisms (like the “pig’s trough” exhaust) and create his own novelties – so, in 1715, recoil escapement, and in 1726 the mercury pendulum. His strong interest in astronomy also pushes him to design precision instruments in this field, including the “astronomical sector” still visible at the Greenwich Observatory.

But for George Graham, clocks are not an end in themselves. Man is set in motion by powerful heart mechanics, making him one of the most generous and altruistic scientists of his time. Not only does he not seek to earn money with his inventions, which he leaves a total free access, but he also participates in the financing of young talents around him. Thus, the same day he is introduced to John Harrison, after several hours talking clocks and clocks, Graham concludes this first interview by giving his young colleague a loan interest free so that he continues his research for the development of the marine chronometer H1. Thereafter, he will not hesitate to let Harrison know about the Longitudes Bureau and to ask for additional financial support for him.

Buried in the same grave as his friend and mentor Thomas Tompion, in Westminster, after his death on November 16, 1751, Graham will become a reference name in the history of watchmaking.

His inventions

Few inventions by George Graham have been crucial.

1915: invention of the recoil anchor escapement for pendulums, known as the “Graham escapement”. This escapement is still used in high precision clocks.

1925: improvement of the exhaust in “pig’s trough”. This escapement, the first cylinder in history, is sometimes attributed, wrongly, to Graham. In fact, this one “only” improved and integrated into one of his clocks in 1715, but it is Thomas Tompion who developed it, and used it in a clock made to the attention by Jonas Moore, as well as two regulators built for the Greenwich Observatory. From 1726, he equips all the watches manufactured by Graham.

1926: invention of the mercury pendulum, known as the Graham pendulum. It reduces the effects of temperature variations. The degree of extreme accuracy achieved by this mechanism, when combined with Graham’s escapement, attributes these clocks to the name of “regulators”. Only the invar, developed by Charles Edward William in 1895, will exceed the accuracy of the mercury pendulum.

Graham has also designed several astronomical vision devices, such as the “Astronomical Sector”, and contributed to the prestige of this discipline. Beyond his inventions that accompanied James Bradley in his celestial discoveries, we owe to Graham the vast wall dial of the Greenwich Observatory, imagined and manufactured at the request of Edmond Halley, as well as the largest planetarium of his time which exhibited the movements of the most precise celestial bodies of the time.

Graham, a name that continues to resonate

Like many inventors of his time, George Graham felt comfortable in many disciplines. That’s why he also has discoveries in geophysics, such as the diurnal variation of the Earth’s magnetic field (around 1722/23), and the fact that this phenomenon is at the origin of the northern lights. He also designed needles for compasses, widely used by specialists of the time.

Despite his entry into the Royal Society in 1721, the twenty-odd articles he published in the scientific journal of the institution, and his many contributions to various fields, the name of George Graham fell somewhat into the forgetfulness when the nerve center of world watchmaking moved from England to Switzerland. It is to the two Swiss entrepreneurs Eric Loth and Pierre-André Finazzi, founders in 1995 of the British Masters, that we must have relaunched Graham’s name – along with other British master watchmakers who have disappeared from the memoirs – to through a collection of high quality watches (more details here).

Français

Français